Dear GlobalEd Readers,

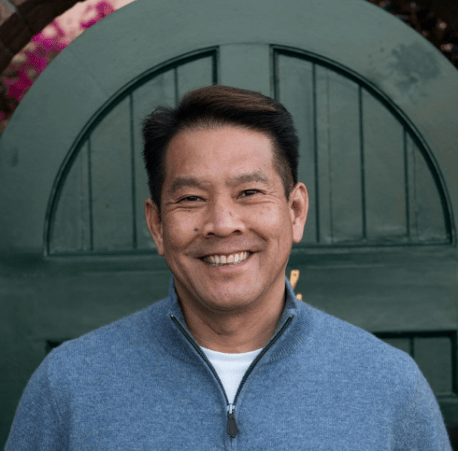

It is such a pleasure to introduce to you one of the most innovative school superintendents in the USA! Dr. David Miyashiro has served as the Superintendent of Cajon Valley Union School District in San Diego, California since 2013, before which he held roles as an assistant superintendent and school principal. He has headed multiple transformational initiatives, programs, and partnerships that have produced a robust digital ecosystem of learning opportunities for teachers and students alike, including establishing the first Computer Science Magnet School in the U.S., pioneering a digital teacher academy, and forging collaborative partnerships with technology vendors for unique 21st-century education opportunities.

So, here’s a chance for you to meet David!

Paula

Back when I was still a school principal, working at a Title I school in Orange County, California, No Child Left Behind had just begun, focusing on standardized testing. There, my superintendent decided we would provide a Mac laptop for every child, also known as one-to-one. The program was intended to be a parent-paid initiative. I spoke with my superintendent, however, and said that my school had a large enough budget to pay for a three-year lease to purchase the computers for our students and close the equity gap between these students and the more affluent ones in other schools in the county.

Shortly after the computers arrived, we realized that our students were incredibly creative, outperforming the more affluent students from other schools. While the affluent students might wait and ask for directions, our students were exploring the technology, teaching themselves, and excelling far past what the teachers knew how to do. We allowed the students to continue this self-discovery and looked to them to help teach us educators. For me, this experience demonstrated the power of what one-to-one looks like in the classroom. As my career path has evolved, from principal to assistant superintendent to my current role in Cajon Valley, I have continued to launch one-to-one initiatives in each place.

When we first pitched the idea of a one-to-one in Cajon Valley Union School District in 2013, we had nearly 1,000 teachers, 18,000 students, and were located in a technology desert. We lacked the devices, infrastructure, training, and pedagogy needed to realize our vision. As part of our implementation strategy, we sent out an interest survey to determine who might take part in our phase one cohort. Much to our surprise, 90% of our staff volunteered — capitalizing on the enthusiasm and buy-in demonstrated, we decided to create a virtual academy where teachers would learn competencies, digital skills, blended and personalized learning models, and how to leverage technology to improve human interactions with students.

In the first iteration of our digital academy, we created digital badges that teachers earned throughout the courses. The first one we made was “Common Core in the Digital Age,” which allowed us to make the shift to using the Common Core curriculum while also helping teachers learn how to incorporate digital tools into their teaching practice. Some of the skills teachers might learn include creating a Google classroom and student roster, and posting images or artifacts on student accounts, among others.

After teachers completed their coursework, we had pairs of teachers teach groups of students in summer school to put those skills into practice. We also interviewed students to learn what was working and how to improve engagement. This approach, developing a digital ecosystem allows more flexibility than traditional professional development models. For example, some teachers enjoy in-person learning while others prefer independent study. Using the MOOC format, badges, and encouraging collaboration provides a hybrid approach that supports varying types of learners.

Today, we have shifted our academy and curriculum to Alludo, which is a gamified site which facilitates our competency-based learning approach. This site has created an archive and improved our ability to train new hires easily. We also partner with Beable, where we developed a million-dollar, globally available K-12 curriculum called “A World of Work.” This curriculum focuses on career development, serving as both a literacy platform for teachers and a training tool for incorporating career development language inside the classroom. Our vision is “Happy kids, healthy relations, on a path to gainful employment.” The foundation of our vision and the curricular resources we provide is vocational psychology and developing an ecosystem of post-secondary opportunities for everybody, rather than pushing the college for all mentality.

In terms of measuring growth and assessing progress with our innovative curriculum and approach, the pandemic has helped us in moving away from traditional monitoring and evaluation practices. Within our district, 43 languages are spoken and many students come from refugee camps, often very far below grade level if assessing them using standardized testing. By teaching educators to use data analytics, machine learning, and data science, we can demonstrate how students are actually making significant progress. We want to focus less on standardized benchmarks and more on individual growth, student interest, and engagement.

Our district’s board gave us permission to look at different metrics and explore alternative evaluation measurements and outcomes. As such, we have been using Beable for diagnostic purposes, as well as real-time progress monitoring to demonstrate personalized growth metrics, both projected and stretch. Teachers are able to think on a continuum, focusing on a student’s long-term growth, rather than preparing them for an end-of-year assessment. This came as a result of community feedback and the San Diego community at-large. For instance, the San Diego Workforce Partnership published a report called “Opportunities,” which focused on students ages 16 to 24 who are neither studying nor working. This is especially prevalent in the parts of the country where there are high poverty rates and joblessness is pervasive. We are working to change these statistics by focusing on engagement, goal setting, and progress monitoring. Such results might not appear on state tests, but would be visible in the Opportunities report through lower poverty rates and improved economic development.

I hope more districts start revisiting how they budget, how curriculum and development are conceptualized, and what types of tools they provide to students. For us, we eliminated the parts of our budget tied to curriculum adoption based on the textbook cycle and used that to fund the one-to-one digital ecosystem and install wifi and other infrastructure. I think that adapting current technology used for medicine and entertainment purposes to education has so far been a missed opportunity, such as using artificial intelligence to make suggestions regarding what students might be interested in reading or learning about, the same way we receive recommendations based on our shopping or viewing habits.

My goal is to make our approach systemic. I think we have an opportunity to change education policy to reflect the new economy and allow every student to have access to gainful employment and financial freedom. Right now, college and career readiness, as well as state standards, do not reflect this approach. Instead, we need to talk more about economic prosperity, financial freedom, and how the school system can help students pursue these goals. By considering what kind of adults we want to produce, I believe we can transform what our K-12 system looks like.

To learn more about Dr. Miyashiro’s work, please visit the district website and/or follow him on twitter.